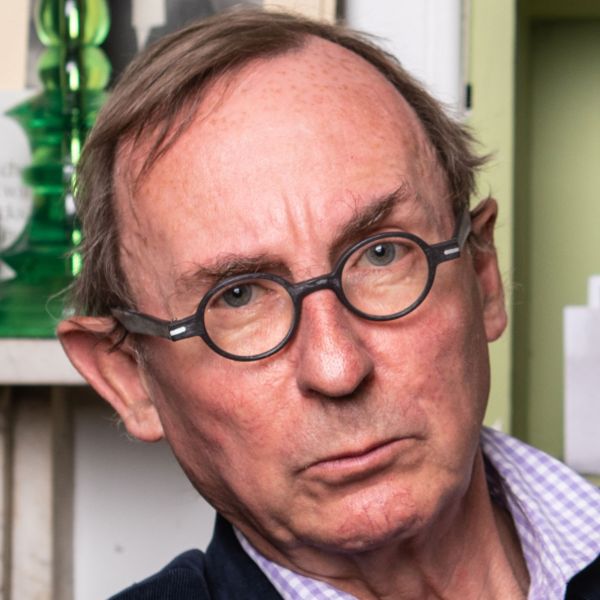

A.N.Wilson on Goethe at Oxford Literary Festival

A.N.Wilson, biographer, novelist and critic, has written more than forty books, and has won the Somerset Maugham Prize, the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize, the Plutarch Award for his biography The Mystery of Charles Dickens, and the Whitbread Prize for his biography of Tolstoy. His latest book, Goethe: His Faustian Life, must arouse intense interest.

When such an erudite and idiosyncratic critic sets to work on one of Europe's greats, what will he come up with?

In his entertaining talk, Wilson surprised most of us by saying that Goethe was as passionately interested in science and philosophy as he was in literature and art. We think of him as an arch-Romantic, but in this respect he saw eye to eye with Enlightenment philosophers such as Voltaire and D'Argens, (both of whom studied science and spent a considerable time in Germany at the Prussian court). Goethe's awe and reverence for Nature did not stop at aesthetic contemplation, but drove him to study it, taking a particular interest in botany.

Goethe was also a very able and energetic administrator, who held a cabinet post in the duchy of Weimar, handling all sorts of practical, legal and financial affairs for many years. I wonder if this side of him explains why he so extravagantly admired Napoleon, despite the humiliating French conquests of Germany and Austria. The French still remember Napoleon as an administrator above all, a ruler who did not only believe in meritocracy but set up a blue-print for how it could be done. If Goethe admired Napoleon uncritically to the very end, he was less politically astute than Beethoven, who burned the dedication to his Eroica Symphony as soon as he heard that the "revolutionary" general had crowned himself Emperor.

We know Goethe of course as a prolific poet and playwright, as well as author of the novel for which he is most often remembered, The Sorrows of Werther. Wilson denies that the huge success of this book really led any young men to kill themselves, but I would not recommend it being set as a study text for impressionable teenagers. There is such a thing as suicide ideation. However, it is certainly unfair to remember Goethe mainly for a book he wrote when he was aged twenty-four. Personally, I am surprised that his later novel Wahlverwandtschaften (Elective Affinities) does not get more attention. It could surely make the basis for a good film.

Wilson pointed out the paradox that Goethe, who has been worshipped by German nationalists, for raising their literature to a level of culture equal to that of any other European country, was not really a nationalist but far more of a pan-European who believed in federation. Perhaps that too explains why he so admired Napoleon. A close relative on every throne across the continent makes for smooth diplomatic relationships. Wilson tells us that Goethe was deeply inspired by his lengthy sojourn in Italy, and he argues that Goethe's encounter there with Classical Hellenistic culture changed his outlook profoundly in mid-life.

Wilson has written in his Confessions: A Life of Failed Promises, that he has a sense of being "a failure... as a writer and as a human being, as a husband, a parent, a son, a friend." Not being able to judge the last five categories, I would say he hasn't done so badly as a writer. His deep pessimism, regarding humans as the blight on this planet, and seeing nothing much in prospect for all of us apart from "dark clouds, dark storms, chaos, disaster and horror" is typical of this post-Covid, global-warming-obsessed era and should not put anyone off reading this latest book. Not if they want to learn about Goethe.

You can buy the book by walking into Blackwells or other good bookshops, or you can order it online from multiple outlets, such as

https://www.worldofbooks.com/en-gb/products/goethe-book-a-n-wilson-9781472994868?

https://oxfordliteraryfestival.org/literature-events/2025/april-01/goethe-his-faustian-life